Echoes of an Ensouled Earth

When the Cosmos Listens Back

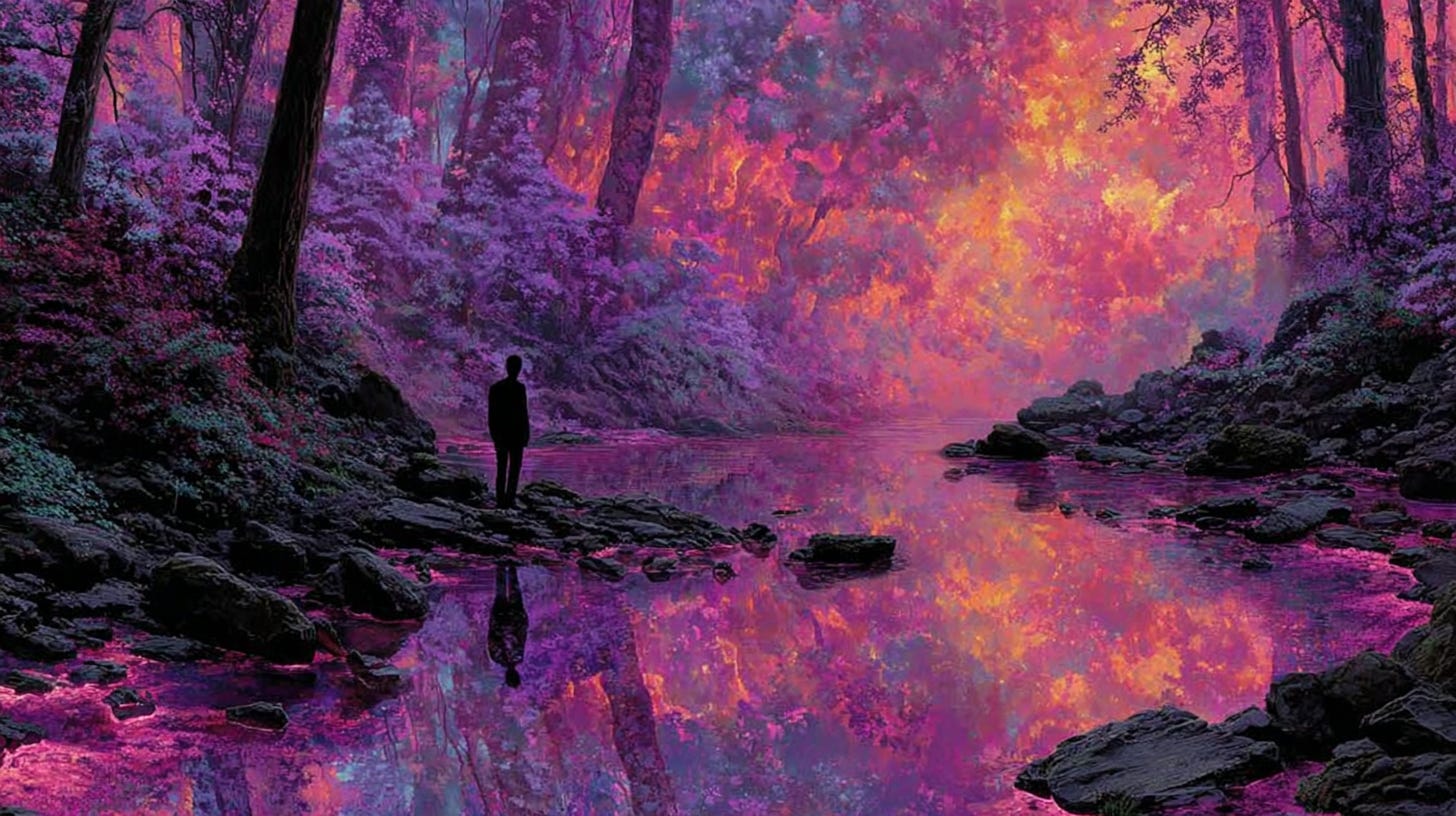

There are days when the world seems dense with meaning. Other times, it feels hollowed out, like something essential has gone missing and no one quite knows where to look for it. I’ve spent years caught between those poles, trying to understand why we so often seem to be talking past one another when we speak about consciousness, about spirit, about what this all is.

It isn’t that anyone’s lying. It’s just that we’re beginning from different assumptions—assumptions we rarely say out loud. But underneath so many conversations—whether about science, spirituality, or experience itself—I often hear a quieter question humming underneath:

Is the world alive—or is it not?

I don’t mean biologically alive. I mean spiritually, cosmologically, meaningfully alive. Is this cosmos inert, accidental, cold? Or is it a living presence—responsive, participatory, even sacred in ways we can’t quite language?

Most of the time, that question isn’t directly asked. But it lives beneath our arguments. It shapes what we allow ourselves to feel. It even shapes what counts as real.

The Living World

I remember when I first encountered Rupert Sheldrake’s work. There was something strangely familiar in his words, as though he were pointing back toward a way of seeing I hadn’t known I’d lost.

In that view, the cosmos is not machinery—it’s memory. It moves not just because of force, but because of resonance. Patterns echo. Consciousness weaves through matter like wind through a grove of trees. The divine isn’t exiled to the afterlife or the abstract—it’s here, now, quietly humming through it all.

And it’s not a new idea. This way of seeing the world as alive—as relational, ensouled—was once common. It still is, in many places. But somewhere along the Western road, something shifted. We grew suspicious of enchantment. Of meaning. Of the sacred.

We began to separate.

Knowledge and Faith, Torn in Two

I think about Descartes sometimes, and not fondly. Not because he was wrong, exactly—but because of what came next. A split opened up: science would concern itself with what could be proven. Faith would be relegated to private belief.

The result was power. We built things. We cured things. We measured the heavens and split the atom. But we also lost something, didn’t we? Not knowledge, but wisdom. Not data, but depth.

We called it enlightenment. But I’ve sat in moments that felt far more luminous—and they had nothing to do with mastery.

The Materialist Spell

When people say “materialist,” I try not to hear it as a slur. It’s a way of knowing, a mode of seeing. It’s coherent in its own terms. It’s just... partial.

Materialism doesn’t mean you don’t feel awe. It doesn’t mean you don’t believe in love or beauty or mystery. It just means you’ve learned to be careful. You keep the inner and the outer on opposite sides of the glass. You don’t conflate your longing with truth.

But I’ve watched people in that mode go through deep psychedelic experiences. I’ve sat with them, before and after. And I’ve seen how something softens—not just emotionally, but ontologically. Like the ground beneath their thinking shifts.

Sometimes it confirms nothing. Sometimes it confirms everything. And sometimes it leaves them with more questions than they knew how to hold.

When the Model Breaks

We often think of belief systems as built. As chosen. But in my experience, they’re more often inherited, absorbed, or shaped by pain. And when something shakes them—really shakes them—it isn’t just intellectual. It’s existential.

I’ve seen materialists emerge from deep journeys trembling. Not because they saw God. Not because they hallucinated the afterlife. But because they glimpsed something they couldn’t fold into their map. A presence. A coherence. A silence that shimmered.

And I’ve seen mystics undone, too. People who were certain the world was alive, who left ceremony unsure if what they’d encountered was Spirit—or just their own longing turned inward.

The medicine does not always affirm what we want it to. It’s not a vending machine for confirmation bias. It’s more like a mirror that won’t lie to you, even when you beg it to.

The Humbling

There’s a particular humility that often comes in the aftermath of these journeys. Not humiliation—but a bowing. A letting go of certainty, not because nothing is true, but because the truth is too large to be held in one hand.

We build models. We speak in metaphors. We study the brain. We pray to the stars. But we are still small creatures, wrapped in skin, trying to name the wind.

And the wind does not care what we name it.

The Edges of Knowing

There’s something peculiar about human consciousness. We can sense what we cannot explain. We can intuit the inconceivable, even as we know we’ll never capture it.

Maybe that’s the heart of it: this aching, beautiful ability to know that we do not fully know. And in that not-knowing, something opens. A tenderness. A reverence. A deeper way of seeing, not because we have the answers—but because we’ve stopped pretending we should.

I’ve watched people come back from the edge of themselves carrying that reverence. A kind of quiet recognition: that the world may be more alive than we are ready to admit.

Not just in metaphor, but in the marrow of things.

Trees that notice. Stones that remember. Animals that grieve. Water that listens. The old myths weren’t all wrong—they just used a different language.

An Unanswered Question

So I’m left with this:

If a worldview is shaped by what it refuses to include...

Then what happens when life offers you something your worldview can’t digest?

Do you dismiss the experience?

Do you revise the map?

Do you carry both, uneasily, as mystery?

I don’t know.

But I think the willingness to live in that question—that quiet, aching tension between what we believe and what we encounter—might be the beginning of something holy.

Not an answer.

But an openness.

And maybe, for now, that’s enough.